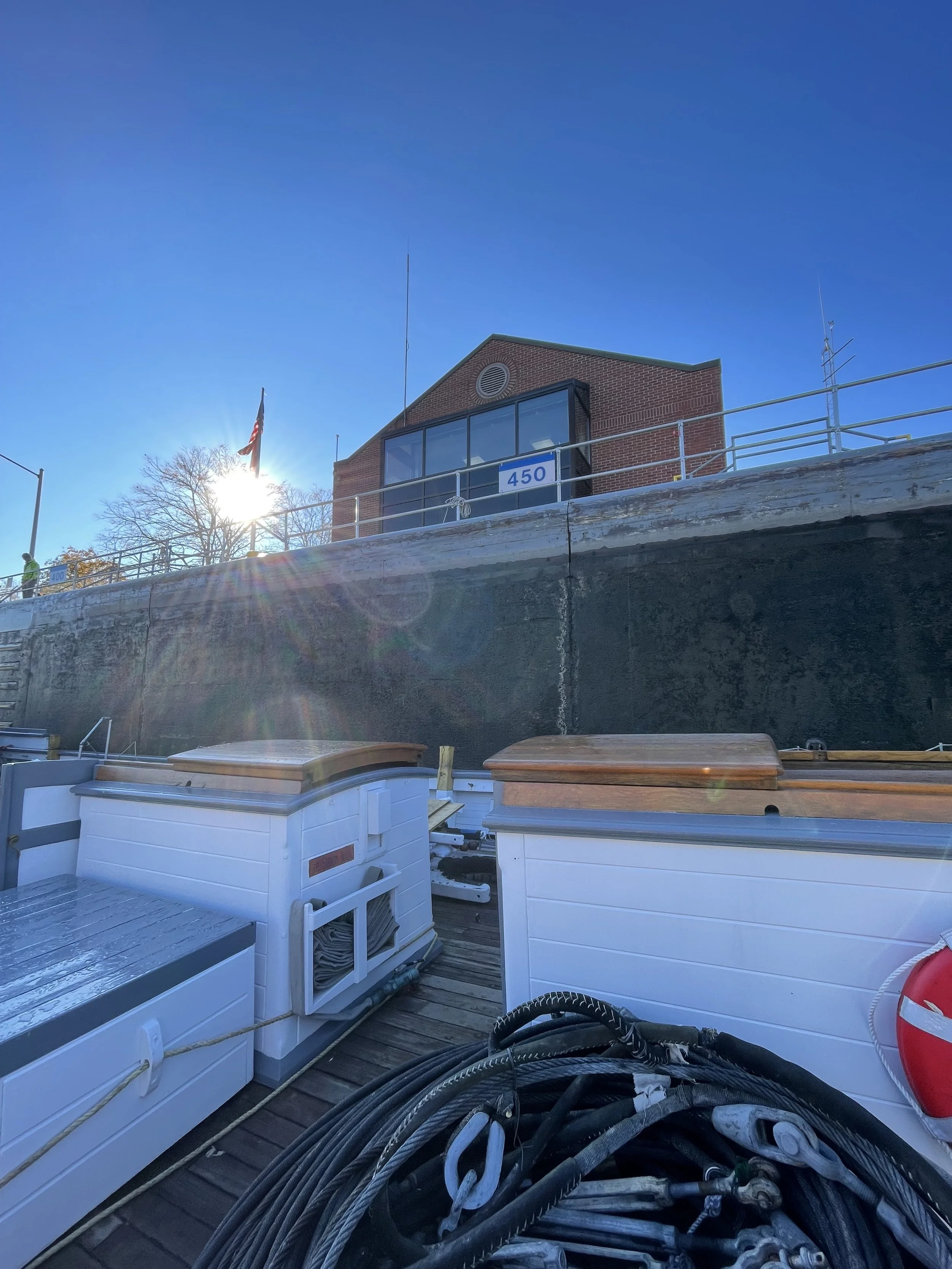

Locks for Newbies (Inland Transit Day 2)

Marseilles Lock and Dam

Marseilles, IL

Log Entry by Program Manager Tatiana Dalton

Wednesday, October 26, 2022

14:10

The first thing I did after sliding out of my bunk today was layer back up for the chilly conditions (wool socks, multiple warm layers on top, my fleece-lined Piers Park Sailing Center hat, and my inflatable safety harness). The second thing I did was climb up on deck to admire our passage through Lock #4 of this voyage—at the Marseille Lock and Dam in Marseilles, Illinois.

While Lock #1 back in Chicago dropped us only 4 feet, we have kicked things up a notch: the Marseille lock lowered the Sullivan—and all of us aboard—24 feet down so that we could continue down the Illinois River.

Hang on—what are locks for, anyway? Well, the short answer is that the Denis Sullivan would make a pretty bad whitewater raft.

The slightly longer answer is that locks exist because even major waterways are sometimes inhospitable to the passage of boats. Obstacles like rapids and sandbars can make it impossible for boats much smaller than the Sullivan to pass through.

One of the most common obstacles, of course, is dams. Whether they are constructed to irrigate crops, generate electricity, or store water for human consumption, dams block the way for boats. In this case, a manmade problem requires a manmade solution, and so many dams are accompanied by a lock. In fact, all of the locks on our route are accompanied by a dam which occupies the rest of the width of the river (hence, the Marseilles Lock and Dam).

We can think of locks moving boats either uphill or downhill—but instead of traveling that vertical distance by going up or down a sloped track, the boats are lifted or lowered in place by a lock. Locks consist of a chamber that boats can enter from either upstream or downstream. Once a boat has entered, the doors close and the chamber water level is either raised (if the boat is traveling upstream) or lowered (if the boat is traveling downstream)—then the other set of doors opens and the boat continues on its way. Here’s a short video from Learn NC of this process.

The chamber at the Marseilles lock is 600 feet long and 110 feet wide, and the lock lowered Denis Sullivan 24 vertical feet. That means that 1,584,000 cubic feet of water—almost 12 million gallons—were drained from the chamber while the Sullivan was inside!

BONUS: Check out this time-lapse of Denis Sullivan passing through Lock #5: Starved Rock Lock in Utica, Illinois!